Accommodative Dysfunction

|

Focusing problem that is unrelated to aging

changes in the lens of the eye.

|

Amblyopia

|

Lazy eye, or amblyopia, is the loss or lack of

development of central vision in one eye that is unrelated to any eye

health problem and is not correctable with lenses. It can result from a

failure to use both eyes together. Lazy eye is often associated with

crossed-eyes or a large difference in the degree of nearsightedness or

farsightedness between the two eyes. It usually develops before the age

of 6, and it does not affect side vision.

Symptoms may include noticeably favouring one eye or

a tendency to bump into objects on one side. Symptoms are not always

obvious.

Treatment for lazy eye may include a combination of

prescription lenses, prisms, vision therapy and eye patching. Vision

therapy teaches the two eyes how to work together, which helps prevent

lazy eye from reoccurring.

Early diagnosis increases the chance for a complete

recovery. This is one reason why the American Optometry Association

recommends that children have a comprehensive optometry examination by

the age of 6 months and again at age 3. Lazy eye will not go away on its

own. If not diagnosed until the pre-teen, teen or adult years, treatment

takes longer and is often less effective.

Early diagnosis increases the chance for a complete recovery. |

Astigmatism

|

Astigmatism is a vision condition that causes

blurred vision due either to the irregular shape of the cornea, the

clear front cover of the eye, or sometimes the curvature of the lens

inside the eye. An irregular shaped cornea or lens prevents light from

focusing properly on the retina, the light sensitive surface at the back

of the eye. As a result, vision becomes blurred at any distance.

Astigmatism is a very common vision condition. Most

people have some degree of astigmatism. Slight amounts of astigmatism

usually don’t affect vision and don’t require treatment. However, larger

amounts cause distorted or blurred vision, eye discomfort and headaches.

Astigmatism frequently occurs with other vision

conditions like nearsightedness (myopia) and farsightedness (hyperopia).

Together these vision conditions are referred to as refractive errors

because they affect how the eyes bend or “refract” light.

The specific cause of astigmatism is unknown. It

can be hereditary and is usually present from birth. It can change as a

child grows and may decrease or worsen over time.

A comprehensive optometric examination will include

testing for astigmatism. Depending on the amount present, your

optometrist can provide eyeglasses or contact lenses that correct the

astigmatism by altering the way light enters your eyes.

Another option for treating astigmatism uses a

corneal modification procedure called orthokeratology (ortho-k). It is a

painless, non-invasive procedure that involves wearing a series of

specially designed rigid contact lenses to gradually reshape the

curvature of the cornea.

Laser

surgery is also a possible treatment option for some types of

astigmatism. It changes the shape of the cornea by removing a small

amount of eye tissue. This is done using a highly focused laser beam on

the surface of the eye.

What causes astigmatism?

When the cornea or lens of an eye is irregularly shaped, vision may be

out of focus at any distance.

Astigmatism occurs due to the irregular shape of

the cornea or the lens inside the eye. The cornea and lens are primarily

responsible for properly focusing light entering your eyes allowing you

to see things clearly.

The curvature of the cornea and lens causes light

entering the eye to be bent in order to focus it precisely on the retina

at the back of the eye. In astigmatism, the surface of the cornea or

lens has a somewhat different curvature in one direction than another.

In the case of the cornea, instead of having a round shape like a

basketball, the surface of the cornea is more like a football. As a

result, the eye is unable to focus light rays to a single point causing

vision to be out of focus at any distance.

Sometimes astigmatism may develop following an eye

injury or eye surgery. There is also a relatively rare condition called

keratoconus where the

cornea becomes progressively thinner and cone shaped. This results in a

large amount of astigmatism resulting in poor vision that cannot be

clearly corrected with spectacles. Keratoconus usually requires contact

lenses for clear vision, and it may eventually progress to a point where

a corneal transplant is necessary.

How is astigmatism diagnosed?

A phoropter and a retinoscope are instruments commonly used by

optometrists to measure refraction.

Astigmatism can be diagnosed through a

comprehensive eye examination.

Testing for astigmatism measures how the eyes focus light and determines

the power of any optical lenses needed to compensate for reduced vision.

This examination may include:

Visual acuity – As part of the testing, you’ll be

asked to read letters on a distance chart. This test measures visual

acuity, which is written as a fraction such as 20/40. The top number is

the standard distance at which testing is done, twenty feet. The bottom

number is the smallest letter size you were able to read. A person with

20/40 visual acuity would have to get within 20 feet of a letter that

should be seen at forty feet in order to see it clearly. Normal distance

visual acuity is 20/20.

Keratometry – A keratometer is the primary

instrument used to measure the curvature of the cornea. By focusing a

circle of light on the cornea and measuring its reflection, it is

possible to determine the exact curvature of the cornea’s surface. This

measurement is particularly critical in determining the proper fit for

contact lenses. A more sophisticated procedure called corneal topography

may be performed in some cases to provide even more detail of the shape

of the cornea.

Refraction – Using an instrument called a

phoropter, your optometrist places a series of lenses in front of your

eyes and measures how they focus light. This is performed using a hand

held lighted instrument called a retinoscope or an automated instrument

that automatically evaluates the focusing power of the eye. The power is

then refined by patient’s responses to determine the lenses that allow

the clearest vision.

Using the information obtained from these tests,

your optometrist can determine if you have astigmatism. These findings,

combined with those of other tests performed, will allow the optometrist

to determine the power of any lens correction needed to provide clear,

comfortable vision, and discuss options for treatment.

How is astigmatism treated?

Persons with astigmatism have several options

available to regain clear vision. They include:

eyeglasses

contact lenses

orthokeratology

laser and other refractive surgery procedures

Eyeglasses are a common form of correction for persons with astigmatism. Eyeglasses are a common form of correction for persons with astigmatism.

Eyeglasses are the primary choice of correction for

persons with astigmatism. They will contain a special cylindrical lens

prescription to compensate for the astigmatism. This provides for

additional lens power in only specific meridians of the lens. An example

of a prescription for astigmatism for one eye would be -1.00 -1.25 X

180. The middle number (-1.25) is the lens power for correction of the

astigmatism. The “X 180” designates the placement (axis) of the lens

power. The first number (-1.00) indicates that this prescription also

includes a correction for nearsightedness in addition to astigmatism.

Generally, a single vision lens is prescribed to

provide clear vision at all distances. However, for patients over about

age 40 who have the condition called

presbyopia, a bifocal or

progressive addition lens may be needed. These provide different lens

powers to see clearly in the distance and to focus effectively for near

vision work.

A wide variety of lens types and frame designs are

now available for patients of all ages. Eyeglasses are no longer just a

medical device that provides needed vision correction. Eyeglass frames

are available in a many shapes, sizes, colors and materials that not

only allow for correction of vision, but also enhance appearance.

For some individuals,

contact lenses can

offer better vision than eyeglasses. They may provide clearer vision and

a wider field of view. However, since contact lenses are worn directly

on the eyes, they require regular

cleaning and care to safeguard eye health.

Soft contact lenses conform to the shape of the

eye, therefore standard soft lenses may not be effective in correcting

astigmatism. However, special toric soft contact lenses are available to

provide a correction for many types of astigmatism. Because rigid gas

permeable contact lenses maintain their regular shape while on the

cornea, they offer an effective way to compensate for the cornea’s

irregular shape and improve vision for persons with astigmatism and

other refractive errors.

Orthokeratology (Ortho-K) involves the fitting of a series of rigid

contact lenses to reshape the cornea, the front outer cover of the eye.

The contact lenses are worn for limited periods, such as overnight, and

then removed. Persons with moderate amounts of astigmatism may be able

to temporarily obtain clear vision without lenses for most of their

daily activities. Orthokeratology does not permanently improve vision

and if you stop wearing the retainer lenses, your vision may return to

its original condition.

Astigmatism can also be corrected by

reshaping the cornea using a

highly focused laser beam of light. Two commonly used procedures are

photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) and laser in situ keratomileusis

(LASIK).

PRK removes tissue from the superficial and inner

layers of the cornea. LASIK does not remove tissue from the surface of

the cornea, but only from its inner layer. To do this, a section of

outer corneal surface is cut and folded back to expose the inner tissue.

Then a laser is used to remove the precise amount of tissue needed and

the flap of outer tissue is placed back in position to heal. Both

procedures allow light to focus on the retina by altering the shape of

the cornea.

Individuals with astigmatism have a wide range of

options to correct their vision problem. In consultation with your

optometrist, you can select the treatment that best meets your visual

and lifestyle needs.

|

Blepharitis

|

Blepharitis is an inflammation of the eyelids

causing red, irritated, itchy eyelids and the formation of dandruff-like

scales on eyelashes. It is a common eye disorder caused by either

bacterial or a skin condition such as dandruff of the scalp or acne

rosacea. It affects people of all ages. Although uncomfortable,

blepharitis is not contagious and generally does not cause any permanent

damage to eyesight.

Blepharitis is classified into two types:

Anterior blepharitis occurs at the outside front

edge of the eyelid where the eyelashes are attached.

Posterior blepharitis affects the inner edge of the

eyelid that comes in contact with the eyeball.

Individuals with blepharitis may experience a

gritty or burning sensation in their eyes, excessive tearing, itching,

red and swollen eyelids, dry eyes, or crusting of the eyelids. For some

people, blepharitis causes only minor irritation and itching. However,

it can lead to more severe signs and symptoms such as blurring of

vision, missing or misdirected eyelashes, and inflammation of other eye

tissue, particularly the cornea.

In many cases, good eyelid hygiene and a regular

cleaning routine can control blepharitis. This includes frequent scalp

and face washing, using warm compresses to soak the eyelids, and doing

eyelid scrubs. In cases where a bacterial infection is the cause,

various antibiotics and other medications may be prescribed along with

eyelid hygiene.

What causes blepharitis?

Blepharitis can appear as greasy flakes or scales around the base of the Blepharitis can appear as greasy flakes or scales around the base of the

eyelashes.

Anterior blepharitis is commonly caused by bacteria

(staphylococcal blepharits) or dandruff of the scalp and eyebrows

(seborrheic blepharitis). It may also occur due to a combination of

factors, or less commonly may be the result of allergies or an

infestation of the eyelashes.

Posterior blepharitis can be caused by irregular

oil production by the glands of the eyelids (meibomian blepharitis)

which creates a favorable environment for bacterial growth. It can also

develop as a result of other skin conditions such as acne rosacea and

scalp dandruff.

How is blepharitis diagnosed?

Blepharitis can be diagnosed through a

comprehensive eye examination.

Testing, with special emphasis on evaluation of the eyelids and front

surface of the eyeball, may include:

Patient history to determine any symptoms the

patient is experiencing and the presence of any general health problems

that may be contributing to the eye problem.

External examination of the eye, including lid

structure, skin texture and eyelash appearance.

Evaluation of the lid margins, base of the

eyelashes and meibomian gland openings using bright light and

magnification.

Evaluation of the quantity and quality of tears for

any abnormalities.

A differentiation among the various types of

blepharitis can often be made based on the appearance of the eyelid

margins:

Staphyloccal blepharitis patients frequently

exhibit mild sticking together of the lids, thickened lid margins, and

missing and misdirected eyelashes.

Seborrheic blepharitis appears as greasy flakes or

scales around the base of eyelashes and a mild redness of the eyelids.

Ulcerative blepharitis is characterized by matted,

hard crusts around the eyelashes that when removed, leave small sores

that ooze and bleed. There may also be a loss of eyelashes, distortion

of the front edges of the eyelids and chronic tearing. In severe cases,

the cornea, the transparent front covering of the eyeball, may also

become inflamed.

Meibomian blepharitis is evident by blockage of the

oil glands in the eyelids, poor quality of tears, and redness of the

lining of the eyelids.

Using the information obtained from testing, your

optometrist can determine if you have blepharitis and advise you on

treatment options.

How is blepharitis treated?

Treatment depends on the specific type of

blepharitis. The key to treating most types of blepharitis is keeping

the lids clean and free of crusts.

Limiting or stopping the use of eye makeup when treating blepharitis is

often recommended, as its use will make lid hygiene more difficult.

Warm compresses can be applied to loosen the

crusts, followed by gentle scrubbing of the eyes with a mixture of water

and baby shampoo or an over-the-counter lid cleansing product. In cases

involving bacterial infection, an antibiotic may also be prescribed.

If the glands in the eyelids are blocked, the

eyelids may need to be massaged to clean out oil accumulated in the

eyelid glands.

Artificial tear solutions or lubricating ointments

may be prescribed in some cases.

Use of an anti-dandruff shampoo on the scalp can

help.

Limiting or stopping the use of eye makeup is often

recommended, as its use will make lid hygiene more difficult.

If you wear contact lenses, you may have to

temporarily discontinue wearing them during treatment.

Some cases of blepharitis may require more complex

treatment plans. Blepharitis seldom disappears completely. Even with

successful treatment, relapses may occur.

Blepharitis seldom disappears completely. Even with

successful treatment, relapses may occur.

Self-care

An important part of controlling blepharitis

involves treatment at home.

Directions for a Warm Soak of the Eyelids:

Wash your hands thoroughly.

Moisten a clean washcloth with warm water.

Close eyes and place washcloth on eyelids for about

5 minutes, reheating the washcloth as necessary.

Repeat several times daily.

Directions for an Eyelid Scrub:

Wash your hands thoroughly.

Mix warm water and a small amount of non-irritating

(baby) shampoo or use a commercially prepared lid scrub solution

recommended by your optometrist.

Using a clean cloth (a different one for each eye)

rub the solution back and forth across the eyelashes and edge of the

closed eyelid.

Rinse with clear water.

Repeat with the other eye.

|

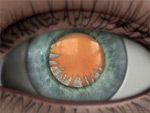

Cataract

|

A cataract is a cloudy or opaque area in the

normally clear lens of the eye. Depending upon its size and location, it

can interfere with normal vision. Most cataracts develop in people over

age 55, but they occasionally occur in infants and young children.

Usually cataracts develop in both eyes, but one may be worse than the

other. Reasearchers have linked eye-friendly nutrients such as

lutein/zeaxanthin,

vitamin C,

vitamin E, and

zinc to reducing the risk of

certain eye diseases, including cataracts. For more information on the

importance of good nutrition and eye health, please see the

diet and nutrition section.

The lens is located inside the eye behind the iris,

the colored part of the eye. The lens focuses light on the back of the

eye, the retina. The lens is made of mostly proteins and water. Clouding

of the lens occurs due to changes in the proteins and lens fibers.

The lens is composed of layers like an onion. The

outermost is the capsule. The layer inside the capsule is the cortex,

and the innermost layer is the nucleus. A cataract may develop in any of

these areas and is described based on its location in the lens:

A nuclear cataract is located in the center of the

lens. The nucleus tends to darken changing from clear to yellow and

sometimes brown.

A cortical cataract affects the layer of the lens

surrounding the nucleus. It is identified by its unique wedge or spoke

appearance.

A posterior capsular cataract is found in the back

outer layer of the lens. This type often develops more rapidly.

|

Types of Cataracts

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nuclear cataract

|

Cortical cataract

|

Posterior capsular cataract

|

Normally, the lens focuses light on the retina,

which sends the image through the optic nerve to the brain. However, if

the lens is clouded by a cataract, light is scattered so the lens can no

longer focus it properly, causing vision problems.

Cataracts generally form very slowly. Signs and

symptoms of a cataract may include:

Blurred or hazy vision

Reduced intensity of colors

Increased sensitivity to glare from lights,

particularly when driving at night

Increased difficulty seeing at night

Change in the eye’s refractive error

While the process of cataract formation is becoming

more clearly understood, there is no clinically established treatment to

prevent or slow their progression. In age-related cataracts, changes in

vision can be very gradual. Some people may not initially recognize the

visual changes. However, as cataracts worsen vision symptoms tend to

increase in severity.

|

Chalazion

|

A chalazion is a slowly developing lump that forms

due to blockage and swelling of an oil gland in the eyelid. It is more

common in adults than children and occurs most frequently in persons 30

to 50 years of age.

Initially, a chalazion may appear as a red, tender,

swollen area of the eyelid. However, in a few days it changes to a

painless, slow growing lump in the eyelid. A chalazion often starts out

very small and is barely able to be seen, but it may grow to the size of

a pea. Often times they may be confused with sties, which are also areas

of swelling in the eyelid.

A sty is an infection of an oil gland in the

eyelid. It produces a red, swollen, painful lump on the edge or inside

surface of the eyelid. Sties usually occur closer to the surface of the

eyelid than do chalazia.

A chalazion is generally not due to an infection,

but results from a blockage of the oil gland itself. However, a

chalazion may occur as an after-effect of a sty.

Common signs or symptoms of a chalazion include:

Appearance of a painless bump or lump in the upper

eyelid, or, less commonly, in the lower eyelid

Tearing

Blurred vision, if the chalazion is large enough to

press against the eyeball

Most chalazia disappear without treatment in

several weeks to a month. However, they often recur. Rarely, they may be

an indication of an infection or skin cancer.

What causes a chalazion?

A chalazion can develop when the oil produced by

glands within the eyelids, called the meibomian glands, becomes

thickened and is unable to flow out of the gland. The oil builds up

inside the gland and forms a lump in the eyelid. Eventually the gland

may break open and release the oil into the surrounding tissue causing

an inflammation of the eyelid.

Risk factors for the development of a chalazion

include:

Chronic blepharitis, an inflammation of the eyelids

and eye lashes

Acne rosacea

Seborrhea

Tuberculosis

Viral infection

How is a chalazion diagnosed?

A chalazion can be diagnosed through a

comprehensive eye examination. Testing, with special emphasis on

evaluation of the eyelids, may include:

Patient history to determine any symptoms the

patient is experiencing and the presence of any general health problems

that may be contributing to the eye problem.

External examination of the eye, including lid

structure, skin texture and eyelash appearance.

Evaluation of the lid margins, base of the

eyelashes and oil gland openings using bright light and magnification.

Using the information obtained from testing, your

optometrist can determine if you have a chalazion and advise you on

treatment options.

How is a chalazion treated?

Many chalazia require minimal medical treatment,

resolving on their own in a few weeks to a month. To facilitate healing,

warm compresses can be applied to the eyelid for 10 to15 minutes 4 to 6

times a day for several days. The warm compresses may help soften the

hardened oil that is blocking the ducts thereby promoting drainage and

healing. Lightly messaging the external area of the eyelid for several

minutes each day may also help to promote drainage.

A clean soft cloth dipped in warm water and wrung

out can serve as an effective compress. Remoisten the cloth frequently

to keep it wet and warm. Once the chalazion drains on its own, keep the

area clean and keep your hands away from your eyes.

If the chalazion does not drain and heal within a

month, contact your eye doctor. Don’t attempt to squeeze or drain the

chalazion yourself.

|

Color Vision Deficiency

|

Color vision deficiency is the inability to

distinguish certain shades of color or in more severe cases, see colors

at all. The term “color blindness” is also used to describe this visual

condition, but very few people are completely color blind.

Red-green deficiency results in the inability to distinguish certain Red-green deficiency results in the inability to distinguish certain

shades of red and green. Most people with color vision deficiency can see

colors, but they have difficulty differentiating between

particular shades of reds and greens (most common)

or

blues and yellows (less common).

People who are totally color blind, a condition

called achromatopsia, can only see things as black and white or in

shades of gray.

The severity of color vision deficiency can range

from mild to severe depending on the cause. It will affect both eyes if

it is inherited and usually just one if the cause for the deficiency is

injury or illness.

Color vision is possible due to photoreceptors in

the retina of the eye known as cones. These cones have light sensitive

pigments that enable us to recognize color. Found in the macula, the

central portion of the retina, each cone is sensitive to either red,

green or blue light, which the cones recognize based upon light

wavelengths.

Normally, the pigments inside the cones register

differing colors and send that information through the optic nerve to

the brain enabling you to distinguish countless shades of color. But if

the cones lack one or more light sensitive pigments, you will be unable

to see one or more of the three primary colors thereby causing a

deficiency in your color perception.

The most common form of color deficiency is

red-green. This does not mean that people with this deficiency cannot

see these colors at all; they simply have a harder time differentiating

between them. The difficulty they have in correctly identifying them

depends on how dark or light the colors are.

Another form of color deficiency is blue-yellow.

This is a rarer and more severe form of color vision loss than red-green

since persons with blue-yellow deficiency frequently have red-green

blindness too. In both cases, it is common for people with color vision

deficiency to see neutral or gray areas where a particular color should

appear.

|

Computer Vision Syndrome

|

A group of eye and vision-related problems that

result from prolonged computer use.

|

Conjunctivitis

|

Conjunctivitis is an inflammation or infection of

the conjunctiva, the thin transparent layer of tissue that lines the

inner surface of the eyelid and covers the white part of the eye.

Conjunctivitis, often called “pink eye,” is a common eye disease,

especially in children. It may affect one or both eyes. Some forms of

conjunctivitis can be highly contagious and easily spread in schools and

at home. While conjunctivitis is usually a minor eye infection,

sometimes it can develop into a more serious problem.

Conjunctivitis may be caused by a viral or

bacterial infection. It can also occur due to an allergic reaction to

irritants in the air like pollen and smoke, chlorine in swimming pools,

and ingredients in cosmetics or other products that come in contact with

the eyes. Sexually transmitted diseases like Chlamydia and gonorrhea are

less common causes of conjunctivitis.

People with conjunctivitis may experience the

following symptoms:

A gritty feeling in one or both eyes

Itching or burning sensation in one or both eyes

Excessive tearing

Discharge coming from one or both eyes

Swollen eyelids

Pink discoloration to the whites of one or both

eyes

Increased sensitivity to light

What causes conjunctivitis?

Allergic Conjunctivitis occurs more commonly among people who already

have seasonal allergies.

The cause of conjunctivitis varies depending on the

offending agent. There are three main categories of conjunctivitis:

allergic, infectious and chemical:

Allergic Conjunctivitis

Allergic Conjunctivitis occurs more commonly among

people who already have seasonal allergies. At some point they come into

contact with a substance that triggers an allergic reaction in their

eyes.

Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis is a type of

allergic conjunctivitis caused by the chronic presence of a foreign body

in the eye. This condition occurs predominantly with people who wear

hard or rigid contact lenses, wear soft contact lenses that are not

replaced frequently, have an exposed suture on the surface or the eye,

or have a glass eye.

Infectious Conjunctivitis

Bacterial Conjunctivitis is an infection most often

caused by staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria from your own skin or

respiratory system. Infection can also occur by transmittal from

insects, physical contact with other people, poor hygiene (touching the

eye with unclean hands), or by use of contaminated eye makeup and facial

lotions.

Viral Conjunctivitis is most commonly caused by

contagious viruses associated with the common cold. The primary means of

contracting this is through exposure to coughing or sneezing by persons

with upper respiratory tract infections. It can also occur as the virus

spreads along the body’s own mucous membranes connecting lungs, throat,

nose, tear ducts, and conjunctiva.

Ophthalmia Neonatorum is a severe form of bacterial

conjunctivitis that occurs in newborn babies. This is a serious

condition that could lead to permanent eye damage unless it is treated

immediately. Ophthalmia neonatorum occurs when an infant is exposed to

Chlamydia or gonorrhea while passing through the birth canal.

Chemical Conjunctivitis

Chemical Conjunctivitis can be caused by irritants

like air pollution, chlorine in swimming pools, and exposure to noxious

chemicals.

How is conjunctivitis diagnosed?

Conjunctivitis can be diagnosed through a comprehensive eye examination.

Conjunctivitis can be diagnosed through a

comprehensive eye examination. Testing, with special emphasis on

evaluation of the conjunctiva and surrounding tissues, may include:

Patient history to determine the symptoms the

patient is experiencing, when the symptoms began, and the presence of

any general health or environmental conditions that may be contributing

to the problem.

Visual acuity measurements to determine the extent

to which vision may be affected.

Evaluation of the conjunctiva and external eye

tissue using bright light and magnification.

Evaluation of the inner structures of the eye to

ensure that no other tissues are affected by the condition.

Supplemental testing may include taking cultures or

smears of conjunctival tissue, particularly in cases of chronic

conjunctivitis or when the condition is not responding to treatment.

Using the information obtained from these tests,

your optometrist can determine if you have conjunctivitis and advise you

on treatment options.

How is conjunctivitis treated?

Treatment of conjunctivitis is directed at three

main goals:

To increase patient comfort.

To reduce or lessen the course of the infection or

inflammation.

To prevent the spread of the infection in

contagious forms of conjunctivitis.

The appropriate treatment for conjunctivitis

depends on its cause:

Allergic conjunctivitis – The first step should be

to remove or avoid the irritant, if possible. Cool compresses and

artificial tears sometimes relieve discomfort in mild cases. In more

severe cases, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications and

antihistamines may be prescribed. Cases of persistent allergic

conjunctivitis may also require topical steroid eye drops.

Bacterial conjunctivitis – This type of

conjunctivitis is usually treated with antibiotic eye drops or

ointments. Improvement can occur after three or four days of treatment,

but the entire course of antibiotics needs to be used to prevent

recurrence.

Viral Conjunctivitis – There are no available drops

or ointments to eradicate the virus for this type of conjunctivitis.

Antibiotics will not cure a viral infection. Like a common cold, the

virus just has to run its course, which may take up to two or three

weeks in some cases. The symptoms can often be relieved with cool

compresses and artificial tear solutions. For the worst cases, topical

steroid drops may be prescribed to reduce the discomfort from

inflammation, but do not shorten the course of the infection. Some

doctors may perform an ophthalmic iodine eye wash in the office in hopes

of shortening the course of the infection. This newer treatment has not

been well studied yet, therefore no conclusive evidence of the success

exists.

Chemical Conjunctivitis – Treatment for chemical

conjunctivitis requires careful flushing of the eyes with saline and may

require topical steroids. The more acute chemical injuries are medical

emergencies, particularly alkali burns, which can lead to severe

scarring, intraocular damage or even loss of the eye.

Contact Lens Wearers

Contact lens wearers may need to discontinue wearing their lenses while

the conjunctivitis is active.

Contact lens wearers may need to discontinue

wearing their lenses while the condition is active. Your doctor can

advise you on the need for temporary restrictions on contact lens wear.

If the conjunctivitis developed due to wearing

contact lenses, your eye doctor may recommend that you switch to a

different type of contact lens or disinfection solution. Your

optometrist might need to alter your contact lense prescription to a

type of lens that you replace more frequently to prevent the

conjunctivitis from recurring.

Self-care

Practicing good hygiene is the best way to control

the spread of conjunctivitis. Once an infection has been diagnosed,

follow these steps:

Don’t touch your eyes with your hands.

Wash your hands thoroughly and frequently.

Change your towel and washcloth daily, and don’t

share them with others.

Discard eye cosmetics, particularly mascara.

Don’t use anyone else’s eye cosmetics or personal

eye-care items.

Follow your eye doctor’s instructions on proper

contact lens care.

You can soothe the discomfort of viral or bacterial

conjunctivitis by applying warm compresses to your affected eye or eyes.

To make a compress, soak a clean cloth in warm water and wring it out

before applying it gently to your closed eyelids.

For allergic conjunctivitis, avoid rubbing your

eyes. Instead of warm compresses, use cool compresses to soothe your

eyes. Over the counter eye drops are available. Antihistamine eye drops

should help to alleviate the symptoms, and lubricating eye drops help to

rinse the allergen off of the surface of the eye.

See your doctor of optometry when you experience

conjunctivitis to help diagnose the cause and the proper course of

action.

|

Convergence Insufficiency

|

An eye coordination problem in which the eyes have

a tendency to drift outward when reading or doing close work.

|

Corneal Abrasion

|

A cut or scratch on the cornea, the clear front

cover of the eye.

|

Crossed Eyes

|

A condition in which both eyes do not look at the

same place at the same time. See also Amblyopia.

|

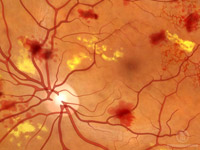

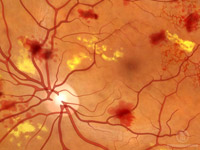

Diabetic Retinopathy

|

Diabetic retinopathy is a condition occurring in

persons with diabetes, which causes progressive damage to the retina,

the light sensitive lining at the back of the eye. It is a serious

sight-threatening complication of diabetes.

Diabetes is a disease that interferes with the

body’s ability to use and store sugar, which can cause many health

problems. Too much sugar in the blood can cause damage throughout the

body, including the eyes. Over time, diabetes affects the circulatory

system of the retina.

Diabetic retinopathy is the result of damage to the

tiny blood vessels that nourish the retina. They leak blood and other

fluids that cause swelling of retinal tissue and clouding of vision. The

condition usually affects both eyes. The longer a person has diabetes,

the more likely they will develop diabetic retinopathy. If left

untreated, diabetic retinopathy can cause blindness.

Symptoms of diabetic retinopathy include:

Seeing spots or floaters in your field of vision

Blurred vision

Having a dark or empty spot in the center of your

vision

Difficulty seeing well at night

In patients with diabetes, prolonged periods of

high blood sugar can lead to the accumulation of fluid in the lens

inside the eye that controls eye focusing. This changes the curvature of

the lens and results in the development of symptoms of blurred vision.

The blurring of distance vision as a result of lens swelling will

subside once the blood sugar levels are brought under control. Better

control of blood sugar levels in patients with diabetes also slows the

onset and progression of diabetic retinopathy.

Often there are no visual symptoms in the early

stages of diabetic retinopathy. That is why the American Optometric

Association recommends that everyone with diabetes have a comprehensive

dilated eye examination once a year. Early detection and treatment can

limit the potential for significant vision loss from diabetic

retinopathy.

Treatment of diabetic retinopathy varies depending

on the extent of the disease. It may require laser surgery to seal

leaking blood vessels or to discourage new leaky blood vessels from

forming. Injections of medications into the eye may be needed to

decrease inflammation or stop the formation of new blood vessels. In

more advanced cases, a surgical procedure to remove and replace the

gel-like fluid in the back of the eye, called the vitreous, may be

needed. A retinal detachment, defined as a separation of the

light-receiving lining in the back of the eye, resulting from diabetic

retinopathy, may also require surgical repair.

If you are a diabetic, you can help prevent or slow

the development of diabetic retinopathy by taking your prescribed

medication, sticking to your diet, exercising regularly, controlling

high blood pressure and avoiding alcohol and smoking.

What causes diabetic retinopathy?

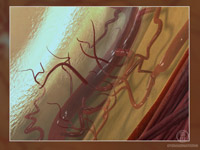

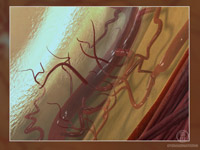

Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) is the early state of the

disease in which symptoms will be mild or non-existent. In NPDR, the

blood vessels in the retina are weakened causing tiny bulges called

microanuerysms to protrude from their walls.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is the more advanced form of

the disease. At this stage, new fragile blood vessels can begin to grow

in the retina and into the vitreous, the gel-like fluid that fills the

back of the eye. The new blood vessel may leak blood into the vitreous,

clouding vision.

Diabetic retinopathy is the result of damage caused by diabetes to the

small blood vessels located in the retina. Blood vessels damaged from

diabetic retinopathy can cause vision loss:

Fluid can leak into the macula, the area of the

retina which is responsible for clear central vision. Although small,

the macula is the part of the retina that allows us to see colors and

fine detail. The fluid causes the macula to swell, resulting in blurred

vision.

In an attempt to improve blood circulation in the

retina, new blood vessels may form on its surface. These fragile,

abnormal blood vessels can leak blood into the back of the eye and block

vision.

Diabetic retinopathy is classified into two types:

Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) is

the early state of the disease in which symptoms will be mild or

non-existent. In NPDR, the blood vessels in the retina are weakened

causing tiny bulges called microanuerysms to protrude from their walls.

The microanuerysms may leak fluid into the retina, which may lead to

swelling of the macula.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is the

more advanced form of the disease. At this stage, circulation problems

cause the retina to become oxygen deprived. As a result new fragile

blood vessels can begin to grow in the retina and into the vitreous, the

gel-like fluid that fills the back of the eye. The new blood vessel may

leak blood into the vitreous, clouding vision. Other complications of

PDR include detachment of the retina due to scar tissue formation and

the development of glaucoma. Glaucoma is an eye disease defined as

progressive damage to the optic nerve. In cases of proliferative

diabetic retinopathy, the cause of this nerve damage is due to extremely

high pressure in the eye. If left untreated, proliferative diabetic

retinopathy can cause severe vision loss and even blindness.

Risk factors for diabetic retinopathy include:

Diabetes — people with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes

are at risk for the development of diabetic retinopathy. The longer a

person has diabetes, the more likely they are to develop diabetic

retinopathy, particularly if the diabetes is poorly controlled.

Race — Hispanic and African Americans are at

greater risk for developing diabetic retinopathy.

Medical conditions — persons with other medical

conditions such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol are at

greater risk.

Pregnancy — pregnant women face a higher risk for

developing diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. If gestational diabetes

develops, the patient is at much higher risk of developing diabetes as

they age.

How is diabetic retinopathy diagnosed?

Diabetic retinopathy can be diagnosed through a comprehensive eye

examination.

Diabetic retinopathy can be diagnosed through a

comprehensive eye examination.

Testing, with special emphasis on evaluation of the retina and macula,

may include:

Patient history to determine vision difficulties

experienced by the patient, presence of diabetes, and other general

health concerns that may be affecting vision

Visual acuity measurements to determine the extent

to which central vision has been affected

Refraction to determine the need for changes in an

eyeglass prescription

Evaluation of the ocular structures, including the

evaluation of the retina through a dilated pupil

Measurement of the pressure within the eye

Supplemental testing may include:

Retinal photography or tomography to document

current status of the retina

Fluorescein angiography to evaluate abnormal blood

vessel growth

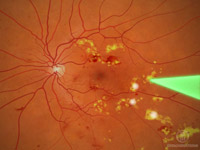

How is diabetic retinopathy treated?

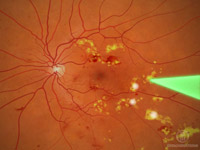

Laser treatment (photocoagulation) is used to stop the leakage of blood

and fluid into the retina. A laser beam of light can be used to create

small burns in areas of the retina with abnormal blood vessels to try to

seal the leaks.

Treatment for diabetic retinopathy depends on the stage of the disease

and is directed at trying to slow or stop the progression of the

disease.

In the early stages of Non-proliferative Diabetic

Retinopathy, treatment other than regular monitoring may not be

required. Following your doctor’s advice for diet and exercise and

keeping blood sugar levels well-controlled can help control the

progression of the disease.

If the disease advances, leakage of fluid from

blood vessels can lead to macular edema. Laser treatment

(photocoagulation) is used to stop the leakage of blood and fluid into

the retina. A laser beam of light can be used to create small burns in

areas of the retina with abnormal blood vessels to try to seal the

leaks.

When blood vessel growth is more widespread

throughout the retina, as in proliferative diabetic retinopathy, a

pattern of scattered laser burns is created across the retina. This

causes abnormal blood vessels to shrink and disappear. With this

procedure, some side vision may be lost in order to safeguard central

vision.

Some bleeding into the vitreous gel may clear up on

its own. However, if significant amounts of blood leak into the vitreous

fluid in the eye, it will cloud vision and can prevent laser

photocoagulation from being used. A surgical procedure called a

vitrectomy may be used to remove the blood-filled vitreous and replace

it with a clearfluid to maintain the normal shape and health of the eye.

Persons with diabetic retinopathy can suffer

significant vision loss. Special low vision devices such as telescopic

and microscopic lenses, hand and stand magnifiers, and video

magnification systems can be prescribed to make the most of remaining

vision.

|

Dry Eye

|

Dry eye is a condition in which there are

insufficient tears to lubricate and nourish the eye. Tears are necessary

for maintaining the health of the front surface of the eye and for

providing clear vision. People with dry eyes either do not produce

enough tears or have a poor quality of tears. Dry eye is a common and

often chronic problem, particularly in older adults.

With each blink of the eyelids, tears are spread

across the front surface of the eye, known as the cornea. Tears provide

lubrication, reduce the risk of eye infection, wash away foreign matter

in the eye, and keep the surface of the eyes smooth and clear. Excess

tears in the eyes flow into small drainage ducts, in the inner corners

of the eyelids, which drain in the back of the nose.

Dry eyes can result from an improper balance of

tear production and drainage.

Inadequate amount of tears – Tears are produced by

several glands in and around the eyelids. Tear production tends to

diminish with age, with various medical conditions, or as a side effect

of certain medicines. Environmental conditions such as wind and dry

climates can also affect tear volume by increasing tear evaporation.

When the normal amount of tear production decreases or tears evaporate

too quickly from the eyes, symptoms of dry eye can develop.

Poor Poor

quality of tears – Tears are made up of three layers: oil, water, and

mucus. Each component serves a function in protecting and nourishing the

front surface of the eye. A smooth oil layer helps to prevent

evaporation of the water layer, while the mucin layer functions in

spreading the tears evenly over the surface of the eye. If the tears

evaporate too quickly or do not spread evenly over the cornea due to

deficiencies with any of the three tear layers, dry eye symptoms can

develop.

The most common form of dry eyes is due to an

inadequate amount of the water layer of tears. This condition, called

keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), is also referred to as dry eye

syndrome.

People with dry eyes may experience symptoms of

irritated, gritty, scratchy, or burning eyes, a feeling of something in

their eyes, excess watering, and blurred vision. Advanced dry eyes may

damage the front surface of the eye and impair vision.

Treatments for dry eyes aim to restore or maintain

the normal amount of tears in the eye to minimize dryness and related

discomfort and to maintain eye health.

What causes dry eyes?

The majority of people over the age of 65 experience some symptoms of

dry eyes.

The development of dry eyes can have many causes.

They include:

Age – dry eye is a part of the natural aging

process. The majority of people over age 65 experience some symptoms of

dry eyes.

Gender – women are more likely to develop dry eyes

due to hormonal changes caused by pregnancy, the use of oral

contraceptives, and menopause.

Medications – certain medicines, including

antihistamines, decongestants, blood pressure medications and

antidepressants, can reduce the amount of tears produced in the eyes.

Medical conditions – persons with rheumatoid

arthritis, diabetes and thyroid problems are more likely to have

symptoms of dry eyes. Also, problems with inflammation of the eyelids (blepharitis),

inflammation of the surfaces of the eye, or the inward or outward

turning of eyelids can cause dry eyes to develop.

Environmental conditions – exposure to smoke, wind

and dry climates can increase tear evaporation resulting in dry eye

symptoms. Failure to blink regularly, such as when staring at a computer

screen for long periods of time, can also contribute to drying of the

eyes.

Other factors – long term use of contact lenses can

be a factor in the development of dry eyes. Refractive eye surgeries,

such as LASIK, can cause decreased tear production and dry eyes.

How are dry eyes diagnosed?

Dry eyes can be diagnosed through a comprehensive

eye examination. Testing, with special emphasis on the evaluation of the

quantity and quality of tears produced by the eyes, may include:

Patient history to determine any symptoms the

patient is experiencing and the presence of any general health problems,

medications taken, or environmental factors that may be contributing to

the dry eye problem.

External examination of the eye, including lid

structure and blink dynamics.

Evaluation of the eyelids and cornea using bright

light and magnification.

Measurement of the quantity and quality of tears

for any abnormalities. Special dyes may be instilled in the eyes to

better observe tear flow and to highlight any changes to the outer

surface of the eye caused by insufficient tears.

Using the information obtained from testing, your

optometrist can determine if you have dry eyes and advise you on

treatment options.

How are dry eyes treated?

One of the primary approaches used to manage and treat mild cases of dry

eyes is adding tears using over-the-counter artificial tear solutions.

Dry eyes can be a chronic condition, but your

optometrist can prescribe treatment to keep your eyes healthy, more

comfortable, and prevent your vision from being affected. The primary

approaches used to manage and treat dry eyes include adding tears,

conserving tears, increasing tear production, and treating the

inflammation of the eyelids or eye surface that contributes to the dry

eyes.

Adding tears – Mild cases of dry eyes can often be

managed using over-the-counter artificial tear solutions. These can be

used as often as needed to supplement natural tear production.

Preservative-free artificial tear solutions are recommended because they

contain fewer additives that could further irritate the eyes. However,

some people may have persistent dry eyes that don’t respond to

artificial tears alone. Additional steps need to be taken to treat their

dry eyes.

Conserving tears – An additional approach to

reducing the symptoms of dry eyes is to keep natural tears in the eyes

longer. This can be done by blocking the tear ducts through which the

tears normally drain. The tear ducts can be blocked with tiny silicone

or gel-like plugs that can be removed, if needed. A surgical procedure

to permanently close tear ducts can also be used. In either case, the

goal is to keep the available tears in the eye longer to reduce problems

related to dry eyes.

Increasing tear production – Prescription eye drops

that help to increase production of tears can be recommended by your

optometrist, as well as omega-3 fatty acid nutritional supplements.

Treatment of the contributing eyelid or ocular

surface inflammation – Prescription eye drops or ointments, warm

compresses and lid massage, or eyelid cleaners may be recommended to

help decrease inflammation around the surface of the eyes.

Self Care

Steps you can take to reduce symptoms of dry eyes

include:

Remembering to blink regularly when reading or

staring at a computer screen for long periods of time.

Increasing the level of humidity in the air at work

and at home.

Wearing sunglasses outdoors, particularly those

with wrap around frame design, to reduce exposure to drying winds and

sun.

Using nutritional supplements containing essential

fatty acids may help decrease dry eye symptoms in some people. Ask your

optometrist if the use of dietary supplements could be of help for your

dry eye problems.

Avoiding becoming dehydrated by drinking plenty of

water (8 to 10 glasses) each day.

|

Farsightedness (Hyperopia)

|

Farsightedness, or hyperopia, as it is medically

termed, is a vision condition in which distant objects are usually seen

clearly, but close ones do not come into proper focus. Farsightedness

occurs if your eyeball is too short or the cornea has too little

curvature, so light entering your eye is not focused correctly.

Common signs of farsightedness include difficulty

in concentrating and maintaining a clear focus on near objects, eye

strain, fatigue and/or headaches after close work, aching or burning

eyes, irritability or nervousness after sustained concentration.

Common vision screenings, often done in schools,

are generally ineffective in detecting farsightedness. A comprehensive

optometric examination will include testing for farsightedness.

In mild cases of farsightedness, your eyes may be

able to compensate without corrective lenses. In other cases, your

optometrist can prescribe eyeglasses or contact lenses to optically

correct farsightedness by altering the way the light enters your eyes.

|

Floaters & Spots

|

Spots (often called floaters) are small,

semi-transparent or cloudy specks or particles within the vitreous,

which is the clear, jelly-like fluid that fills the inside of your eyes.

They appear as specks of various shapes and sizes, threadlike strands or

cobwebs. Because they are within your eyes, they move as your eyes move

and seem to dart away when you try to look at them directly.

Spots are often caused by small flecks of protein

or other matter trapped during the formation of your eyes before birth.

They can also result from deterioration of the vitreous fluid, due to

aging; or from certain eye diseases or injuries.

Most spots are not harmful and rarely limit vision.

But, spots can be indications of more serious problems, and you should

see your optometrist for a comprehensive examination when you notice

sudden changes or see increases in them.

By looking in your eyes with special instruments,

your optometrist can examine the health of your eyes and determine if

what you are seeing is harmless or the symptom of a more serious problem

that requires treatment.

Most spots are not harmful and rarely limit vision. But, spots can be

indications of more serious problems.

|

Glaucoma

|

Glaucoma is a group of eye disorders leading to

progressive damage to the optic nerve, and is characterized by loss of

nerve tissue resulting in loss of vision. The optic nerve is a bundle of

about one million individual nerve fibers and transmits the visual

signals from the eye to the brain. The most common form of glaucoma,

primary open-angle glaucoma, is associated with an increase in the fluid

pressure inside the eye. This increase in pressure may cause progressive

damage to the optic nerve and loss of nerve fibers. Vision loss may

result. Advanced glaucoma may even cause blindness. Not everyone with

high eye pressure will develop glaucoma, and many people with normal eye

pressure will develop glaucoma. When the pressure inside an eye is too

high for that particular optic nerve, whatever that pressure measurement

may be, glaucoma will develop.

Glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness in the U.S. It most

often occurs in people over age 40, although a congenital or infantile

form of glaucoma exists. People with a family history of glaucoma,

African Americans over the age of 40, and Hispanics over the age of 60

are at an increased risk of developing glaucoma. Other risk factors

include thinner corneas, chronic eye inflammation, and using medications

that increase the pressure in the eyes.

The most common form of glaucoma, primary

open-angle glaucoma, develops slowly and usually without any symptoms.

Many people do not become aware they have the condition until

significant vision loss has occurred. It initially affects peripheral or

side vision, but can advance to central vision loss. If left untreated,

glaucoma can lead to significant loss of vision in both eyes, and may

even lead to blindness.

A less common type of glaucoma, acute angle closure

glaucoma, usually occurs abruptly due to a rapid increase of pressure in

the eye. Its symptoms may include severe eye pain, nausea, redness in

the eye, seeing colored rings around lights, and blurred vision. This

condition is an ocular emergency, and medical attention should be sought

immediately, as severe vision loss can occur quickly.

Glaucoma cannot currently be prevented, but if

diagnosed and treated early it can usually be controlled. Medication or

surgery can slow or prevent further vision loss. However, vision already

lost to glaucoma cannot be restored. That is why the American Optometric

Association recommends an annual dilated eye examination for people at

risk for glaucoma as a preventive eye care measure. Depending on your

specific condition, your doctor may recommend more frequent

examinations.

What causes glaucoma?

Glaucoma is the leading cause of blindness among Hispanics.

There are many types of glaucoma and many theories

about the causes of glaucoma. The exact cause is unknown. Although the

disease is usually associated with an increase in the fluid pressure

inside the eye, other theories include lack of adequate blood supply to

the nerve.

Primary open-angle glaucoma – This is the most

common form of glaucoma. One theory is that glaucoma is thought to

develop when the eye’s drainage system becomes inefficient over time.

This leads to an increased amount of fluid and a gradual buildup of

pressure within the eye. Other theories of the cause of the optic nerve

damage include poor perfusion, or blood flow, to the optic nerve. Damage

to the optic nerve is slow and painless and a large portion of vision

can be lost before vision problems are noticed. Other theories also

exist.

Angle-closure glaucoma – This type of glaucoma,

also called closed-angle glaucoma or narrow angle glaucoma, is a less

common form of the disease. It is a medical emergency that can cause

vision loss within a day of its onset.

It occurs when the drainage angle in the eye

(formed by the cornea and the iris) closes or becomes blocked. Many

people who develop this type of glaucoma have a very narrow drainage

angle. With age, the lens in the eye becomes larger, pushing the iris

forward and narrowing the space between the iris and the cornea. As this

angle narrows, the aqueous fluid is blocked from exiting through the

drainage system, resulting in a buildup of fluid and an increase in eye

pressure.

Angle-closure glaucoma can be chronic (progressing

gradually) or acute (appearing suddenly). The acute form occurs when the

iris completely blocks the drainage of the aqueous fluid. In people with

a narrow drainage angle, if their pupils become dilated, the angle may

close and cause a sudden increase in eye pressure. Although an acute

attack often affects only one eye, the other eye may be at risk of an

attack as well.

Secondary glaucoma – This type of glaucoma occurs

as a result of an injury or other eye disease. It may be caused by a

variety of medical conditions, medications, physical injuries, and eye

abnormalities. Infrequently, eye surgery can be associated with

secondary glaucoma.

Normal-tension glaucoma – In this form of glaucoma,

eye pressure remains within what is considered to be the “normal” range,

but the optic nerve is damaged nevertheless. Why this happens is

unknown.

It is possible that people with low-tension

glaucoma may have an abnormally sensitive optic nerve or a reduced blood

supply to the optic nerve caused by a condition such as atherosclerosis,

a hardening of the arteries. Under these circumstances even normal

pressure on the optic nerve may be enough to cause damage.

Risk factors

Certain factors can increase the risk for

developing glaucoma. They include:

Age – People over age 60 are at increased risk for

the disease. For African Americans, however, the increase in risk begins

after age 40. The risk of developing glaucoma increases slightly with

each year of age.

Race – African Americans are significantly more

likely to get glaucoma than are Caucasians, and they are much more

likely to suffer permanent vision loss as a result. People of Asian

descent are at higher risk of angle-closure glaucoma and those of

Japanese descent are more prone to low-tension glaucoma.

Family history of glaucoma – Having a family

history of glaucoma increases the risk of developing glaucoma.

Medical conditions – Some studies indicate that

diabetes may increases the risk of developing glaucoma, as do high blood

pressure and heart disease.

Physical injuries to the eye – Severe trauma, such

as being hit in the eye, can result in immediate increased eye pressure

and future increases in pressure due to internal damage. Injury can also

dislocate the lens, closing the drainage angle, and increasing pressure.

Other eye-related risk factors – Eye anatomy,

namely corneal thickness and optic nerve appearance indicate risk for

development of glaucoma. Conditions such as retinal detachment, eye

tumors, and eye inflammations may also induce glaucoma. Some studies

suggest that high amounts of nearsightedness may also be a risk factor

for the development of glaucoma.

Corticosteroid use – Using corticosteroids for

prolonged periods of time appears to put some people at risk of getting

secondary glaucoma.

How is glaucoma diagnosed?

Glaucoma is diagnosed through a comprehensive eye

examination. To establish a diagnosis of glaucoma, several factors must

be present: Because glaucoma is a progressive disease, meaning it

worsens over time, a change in the appearance of the optic nerve, a loss

of nerve tissue, and a corresponding loss of vision confirm the

diagnosis. Some optic nerves have a suspicious appearance, resembling

nerves with glaucoma, but the patients may have no other risk factors or

signs of glaucoma. These patients should be closely followed with

routine comprehensive exams to monitor for change.

Testing includes:

Patient history to determine any symptoms the

patient is experiencing and the presence of any general health problems

and family history that may be contributing to the problem.

Visual acuity measurements to determine the extent

to which vision may be affected.

Tonometry to measure the pressure inside the eye to

detect increased risk factors for glaucoma.

Pachymetry to measure corneal thickness. People

with thinner corneas are at an increased risk of developing glaucoma.

Visual field testing, also called perimetry, to

check if the field of vision has been affected by glaucoma. This test

measures your side (peripheral) vision and central vision by either

determining the dimmest amount of light that can be detected in various

locations of vision, or by determining sensitivity to targets other than

light, and comparing it to others of similar age.

Evaluation of the retina of the eye, which may

include photographs of the optic nerve, in order to monitor any changes

that might occur over time.

Supplemental testing may include gonioscopy, a

procedure allowing views of the angle anatomy, the area in the eye where

fluid drainage occurs. Serial tonometry may be performed. This is a

procedure acquiring several pressure measurements over time, looking for

changes in the eye pressure throughout the day. Other tests include

using devices to measure nerve fiber thickness, and look for specific

areas of the nerve fiber layer for loss of tissue.

How is glaucoma treated?

The treatment of glaucoma is aimed at reducing

intraocular pressure. The most common first line treatment of glaucoma

is usually prescription eye drops that must be taken regularly. In some

cases, systemic medications, laser treatment, or other surgery may be

required. While there is no cure as yet for glaucoma, early diagnosis

and continuing treatment can preserve eyesight.

Medications – A number of medications are currently

available to treat glaucoma. Typically medications are intended to

reduce elevated intraocular pressure. One may be prescribed a single

medication or a combination of medications. The type of medication may

change if it is not providing enough pressure reduction or if the

patient is experiencing side-effects from the drops.

Surgery involves either laser treatment, making a

drainage flap in the eye, inserting a drainage valve, or destroying the

tissue that creates the fluid in the eye. All procedures aim to reduce

the pressure inside the eye. Surgery may help lower pressure when

medication is not sufficient, however it cannot reverse vision loss.

Laser surgery – Laser trabeculoplasty helps fluid

drain out of the eye. A high-energy laser beam is used to stimulate the

trabecular meshwork to work more efficiently at fluid drainage. The

results may be somewhat temporary, and the procedure may need to be

repeated in the future.

Conventional surgery – If eye drops and laser

surgery aren’t effective in controlling eye pressure, you may need a

filtering procedure called a trabeculectomy. Filtering microsurgery

involves creating a drainage flap, allowing fluid to percolate into and

later drain into the vascular system.

Drainage implants – Another type of surgery, called

drainage valve implant surgery, may be an option for people with

uncontrolled glaucoma, secondary glaucoma or for children with glaucoma.

A small silicone tube is inserted in the eye to help drain aqueous

fluid.

Treatment for acute angle-closure glaucoma

Acute angle-closure glaucoma is a medical

emergency. Several medications can be used to reduce eye pressure as

quickly as possible. A laser procedure called laser peripheral iridotomy

will also likely be performed. In this procedure, a laser beam creates a

small hole in the iris to allow aqueous fluid to flow more freely into

the front chamber of the eye where it then has access to the meshwork

for drainage.

Lifelong treatment

There is no cure for glaucoma. Patients with

glaucoma need to continue treatment for the rest of their lives. Because

the disease can progress or change silently, compliance with eye

medications and eye examinations are essential, as treatment may need to

be adjusted periodically.

By keeping eye pressure under control, continued

damage to the optic nerve and continued loss of your visual field may

slow or stop. The optometrist may focus on lowering the intraocular

pressure to a level that is least likely to cause further optic nerve

damage. This level is often referred to as the target pressure and will

probably be a range rather than a single number. Target pressure differs

for each person, depending on the extent of the damage and other

factors. Target pressure may change over the course of a lifetime. Newer

medications are always being developed to help in the fight against

glaucoma.

Early detection, prompt treatment and regular

monitoring can help to control glaucoma and therefore reduce the chances

of progression vision loss.

|

Hordeolum

|

See Sty

|

Hyperopia (Farsightedness)

|

See Farsightedness

|

Keratitis

|

An inflammation or infection of the cornea, the

clear front cover of the eye.

|

Keratoconus

|

Keratoconus is a vision disorder that occurs when

the normally round cornea (the front part of the eye) becomes thin and

irregular (cone) shaped. This abnormal shape prevents the light entering

the eye from being focused correctly on the retina and causes distortion

of vision.

In its earliest stages, keratoconus causes slight

blurring and distortion of vision and increased sensitivity to glare and

light. These symptoms usually appear in the late teens or late 20s.

Keratoconus may progress for 10-20 years and then slow in its

progression. Each eye may be affected differently. As keratoconus

progresses, the cornea bulges more and vision may become more distorted.

In a small number of cases, the cornea will swell and cause a sudden and

significant decrease in vision. The swelling occurs when the strain of

the cornea’s protruding cone-like shape causes a tiny crack to develop.

The swelling may last for weeks or months as the crack heals and is

gradually replaced by scar tissue. If this sudden swelling does occur,

your doctor can prescribe eyedrops for temporary relief, but there are

no medicines that can prevent the disorder from progressing.

Eyeglasses Eyeglasses

or soft contact lenses may be used to correct the mild nearsightedness

and astigmatism that is caused by the early stages for keratoconus. As

the disorder progresses and cornea continues to thin and change shape,

rigid gas permeable contact lenses can be prescribed to correct vision

adequately. In most cases, this is adequate. The contact lenses must be

carefully fitted, and frequent checkups and lens changes may be needed

to achieve and maintain good vision.

In a few cases, a corneal transplant is necessary.

However, even after a corneal transplant, eyeglasses or contact lenses

are often still needed to correct vision.

|

Lazy Eye (Amblyopia)

|

The loss or lack of development of clear vision in

just one eye. It is not due to eye health problems and eyeglasses or

contact lenses can’t fully correct the reduced vision caused by lazy

eye. See also Amblyopia.

|

Learning-related Vision Problems

|

Vision disorders that interfere with reading and

learning.

|

Macular Degeneration

|

Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) is the

leading cause of severe vision loss in adults over age 50. The Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 1.8 million people have

AMD and another 7.3 million are at substantial risk for vision loss from

AMD. Caucasians are at higher risk for developing AMD than other races.

Women also develop AMD at an earlier age than men. This eye disease

occurs when there are changes to the macula, a small portion of the

retina that is located on the inside back layer of the eye. AMD is a

loss of central vision that can occur in two forms: “dry” or atrophic

and “wet” or exudative.

Most people with macular degeneration have the dry

form, for which there is no known treatment. The less common wet form

may respond to laser procedures, if diagnosed and treated early.

Some common symptoms are: a gradual loss of ability

to see objects clearly, distorted vision, a gradual loss of color

vision, and a dark or empty area appearing in the center of vision. If

you experience any of these, contact your

doctor of optometry

immediately for a comprehensive examination. Central vision that is lost

to macular degeneration cannot be restored. However, low vision devices,

such as telescopic and microscopic lenses, can be prescribed to maximize

existing vision.

Researchers have linked eye-friendly nutrients such

as lutein/zeaxanthin,

vitamin C,

vitamin E, and

zinc to reducing the risk of

certain eye diseases, including macular degeneration. For more

information on the importance of good nutrition and eye health, please

see the diet and nutrition section.

|

Migraine with Aura

|

See Ocular Migraine

|

Myopia

|

Nearsightedness, or myopia, as it is medically

termed, is a vision condition in which close objects are seen clearly,

but objects farther away appear blurred. Nearsightedness occurs if the

eyeball is too long or the cornea, the clear front cover of the eye, has

too much curvature. As a result, the light entering the eye isn’t

focused correctly and distant objects look blurred.

Nearsightedness is a very common vision condition

affecting nearly 30 percent of the U.S. population. Some research

supports the theory that nearsightedness is hereditary. There is also

growing evidence that it is influenced by the visual stress of too much

close work.

Generally, nearsightedness first occurs in

school-age children. Because the eye continues to grow during childhood,

it typically progresses until about age 20. However, nearsightedness may

also develop in adults due to visual stress or health conditions such as

diabetes.

A common sign of nearsightedness is difficulty with

the clarity of distant objects like a movie or TV screen or the

chalkboard in school. A

comprehensive optometric examination will include testing for

nearsightedness. An optometrist can prescribe eyeglasses or contact

lenses that correct nearsightedness by bending the visual images that

enter the eyes, focusing the images correctly at the back of the eye.

Depending on the amount of nearsightedness, you may only need to wear

glasses or contact lenses for certain activities, like watching a movie

or driving a car. Or, if you are very nearsighted, they may need to be

worn all the time.

Another option for treating nearsightedness is

orthokeratology (ortho-k),

also known as corneal refractive therapy. It is a non-surgical procedure

that involves wearing a series of specially designed rigid contact

lenses to gradually reshape the curvature of your cornea. The lenses

place pressure on the cornea to flatten it. This changes how light

entering the eye is focused.

Laser procedures are also a possible treatment for

nearsightedness in adults. They involve reshaping the cornea by removing

a small amount of eye tissue. This is accomplished by using a highly

focused laser beam on the surface of the eye.

For people with higher levels of nearsightedness,

other refractive

surgery procedures are now available. These procedures involve

implanting a small lens with the desired optical correction directly

inside the eye, either just in front of the natural lens (phakic

intraocular lens implant) or replacing the natural lens (clear lens

extraction with intraocular lens implantation). These procedures are

similar to one used for cataract

surgery patients, who also have lenses implanted in their eyes

(intraocular lens implants).

What causes nearsightedness?

If one or both parents are nearsighted, there is an increased chance

their children will be nearsighted.

The exact cause of nearsightedness is unknown, but

two factors may be primarily responsible for its development:

heredity

visual stress